BETA support is for iMac 14,2 / 14,3 (2013), iMac 13,1 / 13,2 (2012) and MacBook Pro 11,3 (2013), MacBook Pro 10,1 (2012), and MacBook Pro 9,1 (2012) users. Compatible GeForce 600 Series: - GeForce GTX 680. Compatible GeForce 200 Series. Currently, the only NVIDIA graphics card that. The Mac Pro 2013 interiors arranged around the thermal core. Even more unusually, the machine has only one (1!) fan that cools everything, wind-tunnel style: So the Mac Pro will, I suspect, be a.

I recently got a high-end 15” Macbook Pro. The 13” model I was using before had served me with faith and dignity over the years, but as my appetite for high-performance apps increased, the poor guy just couldn’t keep up like it used to. In the past, I would have only considered upgrading to another 13” laptop, but a lot has changed over the years. Computers have slimmed down. I’ve slimmed up. A 15” device just didn’t seem like the back-breaking monster it used to be.

The strongest-performing Mac we've tested thus far is a custom-built Late 2013 Mac Pro with an eight-core 3.0GHz Xeon E5 processor, 512GB of flash storage, 32GB of DDR3 memory, and AMD FirePro. Includes NVIDIA Driver Manager preference pane. Includes BETA support for iMac and MacBook Pro systems with NVIDIA graphics; Release Notes Archive: This driver update is for Mac Pro 5,1 (2010), Mac Pro 4,1 (2009) and Mac Pro 3,1 (2008) users. Mac Pro is designed for pros who need the ultimate in CPU performance. From production rendering to playing hundreds of virtual instruments to simulating an iOS app on multiple devices at once, it’s exceedingly capable. At the heart of the system is an Intel Xeon processor with up to 28 cores — the most ever in a Mac.

The other big factor in my decision was graphics performance. Among all the Macbooks currently available, the high-end 15” Macbook Pro is the only one with a discrete graphics chip still inside. You get access to an integrated Intel Iris Pro 5200 for everyday use, but the OS can also switch you over to a powerful Nvidia 750m when the polygons have to fly.

At first, I naturally assumed that the 750m would kick the 5200’s butt; this was a separate ~40w component, after all. But as I started to dig through forum posts and benchmarks for my research, I discovered that while the Iris Pro usually lagged behind the 750m by 15%-50%, there were a few recorded instances where it matched or even surpassed the Nvidia chip! Some people blamed this on drivers, others on architecture. Were the numbers even accurate? I wanted to find out for myself.

There were a couple of specific questions I was looking to answer during my testing:

- How good is the maximum graphics performance of this machine?

- How does the Iris Pro 5200 compare to the 750m?

- How does Windows 7 VM (Parallels) graphics performance compare to native Windows 7 (Bootcamp)?

3DMark

For my first set of benchmarks, I configured a Parallels VM to run off my Bootcamp partition with the following settings: 4 logical processors (which I think gives you 2 physical cores), 12GB RAM, 1GB video memory, DirectX 10, and 1440×900 resolution. (I also ran a test with 2 logical processors, which caused performance issues, and also with 8 logical processors, which caused my system to seriously freeze up.) I then installed the 3DMark demo on Steam and ran the default suite of tests. Finally, I turned off the VM, changed the energy setting from “Better performance” to “Longer battery life” in order to make the VM use integrated graphics (verified with gfxCardStatus), and ran the same tests again.

(Oh, before I give you my results, I should mention that none of these tests are scientifically rigorous. I tried to be as accurate as possible, but I’m no Anand Shimpi. Also, even though the results of my VM tests were consistent with everything else I tried, I’m not sure how much the numbers were skewed given that they were running through Parallels’ DirectX to OpenGL layer.)

| Integrated | Discrete | Discrete Performance Over Integrated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ice Storm | 52223 | 60862 | 116.5% |

| Graphics | 55459 | 69401 | 125.1% |

| Graphics Test 1 | 252.4 fps | 326.2 fps | 129.2% |

| Graphics Test 2 | 230.8 fps | 280.7 fps | 121.6% |

| Cloud Gate | 6035 | 6415 | 106.3% |

| Graphics | 7067 | 7709 | 109.1% |

| Graphics Test 1 | 29.0 fps | 28.6 fps | 98.6% |

| Graphics Test 2 | 32.6 fps | 40.4 fps | 123.9% |

| Physics Test | 12.7 fps | 12.8 fps | 100.8% |

The Physics test only measures CPU speed and can thus be ignored. Insofar as benchmarks are concerned, it looks like the 750m’s gains over the Iris Pro are moderate: 25% in the basic test and 9% in the more intensive test. Do note, however, that the second number is an average, and that Graphics Test 2 in Ice Storm also showed ~25% improvement.

I then ran the same test in native Bootcamp. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to switch to integrated graphics in Windows, so this is only useful for comparing discrete performance between native and VM.

| Discrete | Windows Native Performance Over Windows VM | |

|---|---|---|

| Ice Storm | 80004 | 131.5% |

| Graphics | 101785 | 146.7% |

| Physics | 45745 | 107.5% |

| Graphics Test 1 | 447.9 fps | 137.3% |

| Graphics Test 2 | 437.3 fps | 155.8% |

| Physics Test | 145.2 fps | 107.5% |

| Cloud Gate | 10258 | 159.9% |

| Graphics | 12601 | 163.5% |

| Physics | 6215 | 153.8% |

| Graphics Test 1 | 55.0 fps | 192.3% |

| Graphics Test 2 | 54.6 fps | 135.1% |

| Physics Test | 19.7 fps | 153.9% |

As one might expect, Bootcamp clobbers Parallels. The more demanding Cloud Gate benchmark shows much bigger gains than Ice Storm, implying that the VM is better suited to slightly older games.

3DMark in Bootcamp also added one more test at the end, possibly due to the fact that Parallels only supports DirectX 10. I’m putting it here for completion’s sake.

| Discrete | |

|---|---|

| Fire Strike | 1741 |

| Graphics | 1790 |

| Physics | 9024 |

| Combined | 721 |

| Graphics Test 1 | 8.3 fps |

| Graphics Test 2 | 7.32 fps |

| Physics Test | 28.6 fps |

| Combined Test | 3.35 fps |

Unigine Heaven

Refurbished Mac Pro 2013

Next, I downloaded the Unigine Heaven benchmark. This benchmark is very convenient because it can be run natively in both Windows and OSX, allowing us to make cross-platform comparisons.

First, I ran the same Parallels test that I did for 3DMark using Unigine’s two built-in presets. Unfortunately, it turned out that the Extreme test didn’t support tesselation in VM but did when run natively, forcing me to do a few custom runs on the other platforms with tesselation turned off. It also threw up errors when I tried to run the test in OpenGL or DirectX 9, so I had to stick to DirectX 11 in the VM.

| Integrated | Discrete | Discrete Performance Over Integrated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic (DirectX 9) | 660 (26.2 fps) | 856 (34.0 fps) | 129.7% |

| Extreme (DrectX 11 Without Tesselation) | 241 (9.6 fps) | 416 (16.5 fps) | 172.6% |

A surprisingly significant result for the Extreme benchmark! Discrete performance is nearly twice as fast.

Next, I did the same test in OSX, using the ever-so-convenient gfxCardStatus to switch between integrated and discrete graphics.

| Integrated | Discrete | Discrete Performance Over Integrated | OSX Integrated Performance Over Windows VM Integrated | OSX Discrete Performance Over Windows VM Discrete | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic | 543 (21.6 fps) | 870 (34.5 fps) | 160.2% | 82.3% | 101.6% |

| Extreme (OpenGL) | 157 (6.2 fps) | 271 (10.8 fps) | 172.6% | ||

| Extreme (OpenGL Without Tesselation) | 230 (9.1 fps) | 384 (15.2 fps) | 167.0% | 95.4% | 92.3% |

Yikes! Looks like running a benchmark tool in a VM, through Parallels’s DirectX to OpenGL layer, and finally through the OSX OpenGL driver is somehow faster than running the same benchmark natively. On the other hand, the difference between integrated and discrete performance is a lot more consistent here. Like in the previous test, we see almost twofold gains.

Finally, I ran the same test in Bootcamp.

| Discrete | Windows Native Performance Over Windows VM | Windows Native Performance Over OSX |

|---|---|---|

| Basic (OpenGL) | 971 (38.5 fps) | 111.6% |

| Basic (DirectX 9) | 994 (39.5 fps) | 116.1% |

| Extreme (OpenGL) | 298 (11.8 fps) | 110.0% |

| Extreme (DirectX 11 Without Tesselation) | 465 (18.5 fps) | 111.8% |

Looks like the difference between all three platforms for this particular benchmark isn’t too significant.

Metro: Last Light

For my next test, I decided to go a little crazy and give Metro: Last Light a go. Frankly, I wasn’t even sure if Parallels was up to the task! As it turns out, modern VMs are a lot more powerful than they look.

Here are the presets I used with the handy MetroLLbenchmark.exe utility.

- Preset 1: 1440×900, DirectX 10, low quality, AF 4×, low motion blur, SSAA off, PhysX off

- Preset 2: 1440×900, DirectX 10, high quality, AF 16×, normal motion blur, SSAA off, PhysX off

- Preset 3: 1920×1200, DirectX 10, high quality, AF 16×, normal motion blur, SSAA on, PhysX off

And here are the results with the typical Parallels shenanigans.

| Integrated | Discrete | Discrete Performance Over Integrated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preset 2 | 10.82 fps (1657 frames) | 18.7 fps (2940 frames) | 172.8% |

| Preset 3 | 3.89 fps (589 frames) | 6.6 fps (1023 frames) | 169.7% |

As with Unigine, we see almost twofold gains when using discrete graphics. Makes sense: Metro is one of the most graphically intensive games on PC right now.

Next, I ran all my presets in Bootcamp.

| Discrete | Windows Native Performance Over Windows VM | |

|---|---|---|

| Preset 1 | 43.74 fps (7480 frames) | |

| Preset 2 | 27.76 frames (4744 frames) | 148.4% |

| Preset 3 | 9.54 fps (1624 frames) | 144.5% |

I was surprised to see that the gain from running natively over running in VM was only around 50%. For a game like Metro, I expected native Windows to completely blow the VM away. You probably wouldn’t want to run the game in Parallels due to the fact that it’s a bit jittery and unstable, but still!

Just to see how far I could push this machine, I added a couple of modified runs: Preset 2 with SSAA on, and Preset 2 with PhysX on.

| Discrete | Modified Preset Performance Over Preset 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Preset 2 (SSAA on) | 16.22 fps (2767 frames) | 58.4% |

| Preset 2 (PhysX on) | 21.69 fps (3706 frames) | 78.1% |

If you’re going for performance, SSAA is clearly a killer. PhysX, on the other hand, doesn’t make as much of an impact as I expected. Still might be worth turning off: I didn’t notice anything different in the benchmark.

Just for kicks, I did one more batch of runs in DirectX 11 mode.

| Discrete | DirectX 11 Performance Over DirectX 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Preset 1 | 44.91 fps (7679 frames) | 102.7% |

| Preset 2 | 29.74 frames (5083 frames) | 107.1% |

| Preset 2 (SSAA on) | 17.58 fps (3002 frames) | 108.4% |

| Preset 3 | 10.58 fps (1803 frames) | 110.9% |

Whoa! It actually runs better? Definitely wasn’t expecting that. Certainly not the case on my desktop.

I would have loved to test the performance of Metro on OSX, but unfortunately the OSX port had no benchmark tool and barely offered any graphics options to speak of.

Batman: Arkham City

Finally, I found the one recent game in my Steam library that had an in-game benchmark on OSX: Batman: Arkham City. I ran it on the Low and High presets in 1680×1050.

| Integrated | Discrete | Discrete Performance Over Integrated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 37 fps | 54 fps | 145.9% |

| High | 32 fps | 44 fps | 137.5% |

The Unreal 3 engine isn’t as fancy as the Metro engine and the benchmarks reflect this. Discrete performance is “only” around 40% faster than integrated.

A few more telling benchmarks would be Far Cry 3, Crysis 2/3, Battlefield 3/4, and Max Payne 3. These represent some of the most powerful engines available on PC right now. I might add a few more measurements later on.

Conclusion

There you have it! A bit of benchmark geekery to shed some light on the new Macbook Pro’s graphics situation. What have we learned?

- The Nvidia 750m is significantly better than the Intel Iris Pro 5200 in many cases, surpassing it by 25%-70% in framerate. With that said, the Iris Pro is powerful enough to run most of the same games at lower settings, which is all the more impressive considering its very low power consumption. I would frankly be surprised if the next generation of Macbook Pros even had a discrete graphics chip, and given the speed at which Intel is improving their graphics performance, that might be OK by me.

- Bootcamp performs a whole lot better than Parallels, generally by 50%-60%. Performance is also a lot smoother. Still pretty darn impressive, considering that the VM boots up in about 5 seconds and hangs out in your dock while Bootcamp requires closing all your applications and rebooting. For the vast majority of Windows applications, Parallels looks like the winner. (Side note: I noticed really frustrating controller lag in Spelunky until I disabled vertical synchronization in the VM options. Unfortunately, this caused some pretty heavy tearing.)

- I wasn’t specifically testing for it since I knew the answer already, but OSX really suffers in graphics performance compared to Windows. The state of Mac ports in general is honestly a bit sad. Many of them run in a compatibility layer like Wine instead of running natively. Saves usually aren’t synced between Mac and Windows. Graphics menus often leave you with far fewer choices, going so far as a single-axis slider for Metro. Crashes and other bizzare problems frequently show up. Unless you’re playing games by Valve or Blizzard, you’ll be better off running in Bootcamp or Parallels. (And even then, I’ve noticed weird mouse behavior, network errors, and outright crashes in the Mac port of Counter-Strike: Global Offensive!)

- In terms of hardware, Macs haven’t traditionally been known for their gaming prowess, but all that’s changed. If I can run Metro, I can call this a gaming machine. End of story.

There are a few other subtle advantages and disadvantages that the discrete graphics chip brings to the table. I might as well mention them here.

- Pro: OpenCL can allegedly use both the integrated and discrete chips simultaneously. Apple seems to be pushing for OpenCL these days, so we may see significant performance gains in this area as high performance apps catch up. Hopefully, the new Mac Pro will be a cataclyst for this.

- Con: Discrete graphics really eat through your battery life. While most applications don’t automatically switch to discrete graphics, some do and won’t switch back until you close them. As far as I know, the only easy way to tell which chip is currently active is to use gfxCardStatus. You can also use this tool to force OSX into integrated graphics mode, unless you’re hooked up to an external monitor. However, there’s no guarantee that this workaround will keep working with future OS updates!

- Con: In Bootcamp, you can’t switch to integrated graphics. This means that if you run your top-of-the-line Macbook in Windows, you’ll have poor battery life. Not so if you buy a Macbook without discrete graphics.

Finally, a quick note on the day-to-day performance of this machine. Holy matchsticks, is it fast! I didn’t realize it was even possible to boot up a VM in 5 seconds, let alone run a game like Metro on it. On my previous machine, a mid-range Core2Duo with 8GB RAM, booting up the VM was an ordeal, and often left one OS or the other in an unusable state. Here, it’s as smooth as opening any other app. In terms of game performance, I’m super impressed by how well most of my favorite games run, even compared to my desktop. Lightroom is blazing fast when browsing and developing, though full-size previews for my 8MP photos take a second each to generate. And, of course, the Retina display is stunningly beautiful, though it does seem a bit darker than the screen on my previous laptop. Might just be a trick of the eye.

(One minor Bootcamp issue: Windows 7 doesn’t deal with DPI scaling very well, so running at the native 2880×1800 with 200% DPI looks kinda bad. Unfortunately, the halved 1440×900 isn’t a standard resolution according to the Nvidia driver and looks a bit blurry. Since anything other than 2880×1800 was going to be blurry anyways, I’ve resorted to running in 1680×1050. Interestingly, since the Windows VM uses Parallels’ own graphics driver, it does not have this problem at 1440×900.)

External Gpu For Mac Pro 2013

I realize this is one of the most expensive machines on the market, but if you want something that can develop OSX/iOS apps and run Windows and play all your games and be compact enough to travel with for long periods of time and have enough screen estate to do serious work… [deep breath]… and have a beautiful and sturdy design that will last you many years, this laptop truly has no equals. Price is a tough pill to swallow, though.

Other References

- Notebookcheck’s benchmarks for the Iris Pro 5200 and the 750m. Their measured gains are a lot more modest than mine, but the benchmarks also older and done on different machines.

- MacRumors has a fewusefulthreads dealing with the Iris Pro/750m question.

Hell finally froze over yesterday and Apple announced a new Mac Pro at WWDC. At first glance, the new machine was as mysterious as it was terrifying to me and many other creative pros who have been waiting for ages for this thing to drop. But now that Apple has a full site page for the new machine and I’ve gotten some info from people familiar with its internals and with OS X 10.9, the Mac Pro has become less of a mystery.

Nvidia For Mac Pro 2013 Download

But that’s also what’s freaking us out.

The design

At 6.6' × 9.9' for its cylindrical stretched aluminum case, the new Mac Pro is tiny, and no other workstation-class Xeon desktop with a discrete workstation GPU—or two, in this case—looks anything like it. You get the feeling that the designers sat around coming up with ideas for the new Mac Pro and said, “If Darth Vader edited video, what would his computer look like?” Well... it would probably look like this:

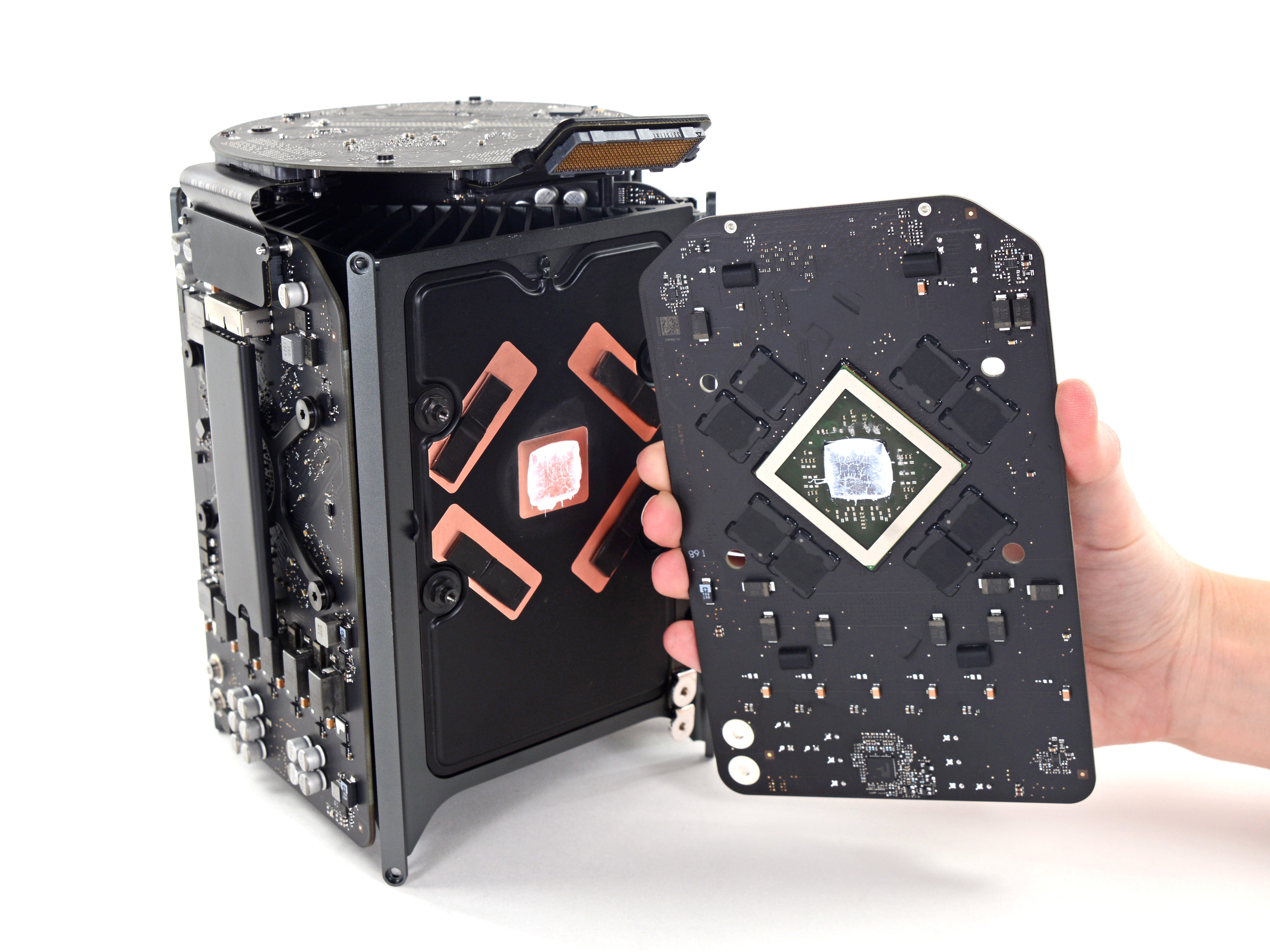

If you haven’t seen the inside already, it’s a truly amazing bit of engineering, organized in a tube-like shape with a triangular arrangement of the motherboard elements along the exterior walls of the “thermal core,” a unibody-like heatsink that draws heat away from the GPU, CPU, and memory:

Even more unusually, the machine has only one (1!) fan that cools everything, wind-tunnel style:

So the Mac Pro will, I suspect, be a ridiculously quiet workstation as well. This is Apple engineering at its best, and I won’t have any concerns about using this for long sessions of V-Ray rendering or ZBrush sculpting. Detractors will say it’s going to overheat if you do anything serious, but Apple knows these things need to run around the clock for days on end. It didn’t put a dual workstation GPU in there and expect people not to use it extensively. More about that further on.

The new Mac Pro makes the previous generation look (thankfully) as outdated as it should, given that the machine it’s replacing uses technology from 2010. All the expected modern technologies are here, plus some that will put the new machine ahead of many current competing workstations: dual Gigabit Ethernet, HDMI 1.4, Thunderbolt 2.0 with DisplayPort 1.2 support for up to three 4K displays, 802.11ac wireless, Bluetooth 4.0, 1866MHz ECC RAM, PCIe-based flash storage, and dual AMD FirePro GPUs with up to 6GB of VRAM. The addition of WiFi as standard is a nice addition, but it’s kind of a gimme considering the machine's lack of upgradeability.

Judging by the animation on Apple’s site, the RAM also appears to be easily user-replaceable:

Apple opted to build in PCIe-based flash storage, and it appears to be on a daughter card:

Performance-wise, the move to PCIe-based internal storage as standard was really smart. Since SATA3 tops out at 600MBps, it’s soon going to be the weakest link as the next generation of SSDs start to push beyond that range. Considering that Apple uses fast Samsung SSDs as standard in its laptops, I’m sure the company will slap a very fast SSD in the new Mac Pro. Expect companies like OWC to make Mac Pro-specific flash storage upgrades after the machine launches.

As far as the other technologies go, it’s clear that Apple is pulling out all the stops to make the Mac Pro a serious professional’s tool that won’t get dated any time soon. Which is good, because the stuff inside it better last...

A truly epic lack of expandability

Ask any Mac Pro users where “small size” sits on their list of workstation needs and they will tell you it's down at the bottom, squarely between “should make my bed in the morning” and “covered in fur.” The added desktop space will be nice to make room for those three shiny 4K displays that we can apparently afford, but “tiny” isn’t on my list of wants for a workstation. Fortunately for me, “rack-mountable” isn’t on there either, since cylindrical isn’t the most server-ready format.

But the small size creates a potential problem. Aside from the regressive lack of any easily accessible ports on the front of the machine, the new Mac Pro has some serious expandability issues.

Internal hard drives

I’m personally on the fence about this one and see it as more of a nuisance than a showstopper. Most professional video people use external RAID arrays for their video work, and the new Mac Pro’s six Thunderbolt 2 ports will provide more than enough expandability to accommodate them.

But I don’t do much video work, and the four internal drive bays of the existing Mac Pro enclosure became a comfy standard for me and my work. Anything more seems like too many—but zero extra drive bays is, to put it mildly, too few. Now I will be forced to replace my existing eSATA RAID enclosure since eSATA/Thunderbolt adapters are stupidly expensive and there are no PCI slots in the machine to accommodate an eSATA adapter card. Considering the still-high price of external Thunderbolt enclosures, the price of the Mac Pro better be reasonable, because it’s clear that many of us will be forced to take this route as well.

I think that Apple is doing two things with this approach to expandability: one, it hopes to light a fire under third-party Thunderbolt supporters the way it did with USB and the iMac. Two, it wants to drive a wedge between professional video on the Mac (still the standard, regardless of how many times you troll me) and video editing on the PC. Many tools that were once PCI-only have been moved to an external Thunderbolt enclosure, much like how audio cards for FireWire and USB became the norm in mobile music. I’m sure that Apple’s move with the Mac Pro was meant to help accelerate that trend so that the Mac Pro and MacBook Pro can share formerly PCI-based video hardware. For many devices, the 20Gbps bandwidth of Thunderbolt 2 will be fine for this purpose, but those will also cost more than a vanilla PCI card.

It seems that the price of the new Mac Pro keeps rising.